Not long after Aimee McQuilken and her daughters touched down in Texas for a mid-March family visit, the NBA announced it was suspending the 2020 season in response to the coronavirus pandemic. McQuilken’s mind immediately shot back to her home in Missoula, and her long-standing clothing boutique on the popular riverside retail corridor known as the Hip Strip. Betty’s Divine had just spent all its cash and maxed out its credit line on new clothes for the spring season, anticipating the warm-weather uptick in sales that’s become part of the shop’s seasonal ebb and flow since McQuilken opened the doors in 2005.

“In some senses it was the worst timing,” McQuilken said of the pandemic’s rapid proliferation and sudden arrival in Montana. “I had no extra cash, and the main thing was, ‘what the heck are my employees going to do?’”

McQuilken quickly contacted her banker at Clearwater Credit Union to extend her business’ line of credit. When she returned to Montana on March 18, Gov. Steve Bullock’s traveler quarantine and shelter-in-place directives were still days away, but she simultaneously closed the shop and went into a self-imposed two-week isolation. Then the hard work began. Her staff of five filed for unemployment, as did McQuilken. With the help of her banker and the Missoula-based financial assistance nonprofit MoFi, she turned her application for a federal Paycheck Protection Program loan around in one day, and began selling clothes through the Betty’s Divine Instagram page. Throughout April, her teenage daughter logged driving time on her learner’s permit by chauffeuring McQuilken around town on clothing deliveries.

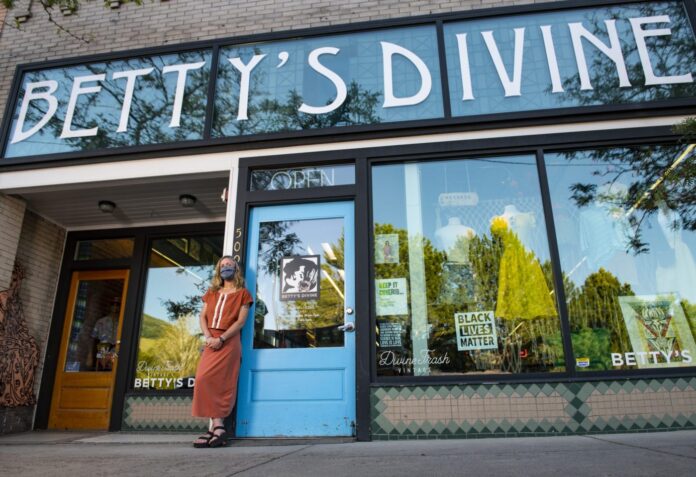

The part McQuilken really struggled with, though, came in May as businesses statewide gradually started reopening. As a clothing retailer, McQuilken said, Betty’s Divine had never had to deal with rigorous sanitation protocols like those laid out by the Missoula City-County Health Department. They’d vacuumed floors and washed windows, but face masks, regularly sanitized surfaces and social distancing were a whole new world. So McQuilken turned to a new COVID-19-specific resource for guidance, one developed to assist Missoula businesses in tackling the manifold challenges raised by the pandemic.

A BEAR OF A SOLUTION

Housed at the University of Montana, the COVID-19 Business Emergency Assistance & Recovery program — or BEAR — emerged during the early days of the pandemic in response to the ever-shifting landscape of financial tools churned out at the federal and state levels. Aware that business owners already stressed by the impacts of coronavirus might not have the easiest time mapping their own path through the crisis, Missoula Economic Partnership Executive Director Grant Kier reached out to business leaders on the University of Montana campus to discuss a one-stop shop for information businesses might need to weather the immediate storm. According to one of those leaders, Paul Gladen of the UM-based business nonprofit Blackstone LaunchPad, the BEAR program was up and running within a week of Kier’s request, offering a online storehouse of all things COVID relief and posting videos on YouTube of Missoula business owners sharing stories of adjusting to a pandemic economy. Some of those same people were quickly stationed on a BEAR roundtable, a working group designed to coordinate with economic development organizations and the hastily formed Missoula County Economic Recovery Task Force.

“The BEAR program, in some ways, was almost sort of a branding exercise to help people understand there was a single point that they could go to to get help,” Gladen said. “Sometimes it can be a little confusing for businesses to know exactly where to go, so that was part of our objective in putting the BEAR program together.”

Throughout April and May, the BEAR program assisted local business owners in identifying the best resources to fit their needs. The federal CARES Act initially allocated nearly $350 billion to the Paycheck Protection Program, radically expanded eligibility for the Economic Injury Disaster Loan program and set up several other loan and debt forgiveness opportunities through the U.S. Small Business Administration. In Montana, the Bullock administration rolled out program after program — a total of 12 to date — each tailored to meet a specific need including loan deferment, immediate stabilization for existing businesses, and longer term adaptation to the new realities of a COVID-19 world. Grant awards in Missoula County alone currently total $8.8 million, more than $7.4 million of which has been allocated through the Business Stabilization Program. As of July 7, those grant programs — backed by CARES Act relief funds — paid out $65 million to businesses statewide.

ALL HANDS ON DECK

Businesses aren’t the only ones scrambling to navigate these new emergency resources. Tara Rice, director of the Montana Department of Commerce, estimates her agency has been processing 200 to 300 applications a day for the grant programs it administers. Prior to the pandemic, that was typically the number of grants the department processed in a full year.

“We’ve reassigned the bulk of people who work within the Department of Commerce to work on these special grant programs,” Rice said. “Many of them are still sustaining the other programs that they run … but we’ve internally reassigned as many people as we can and redeployed our whole department around this effort. At any given time, we’ll have 60 or more people on detail from other parts of state government assisting the Department of Commerce with getting these programs out, and that’s just for two of the 12 grant programs.”

At the onset of the pandemic, Jennifer Stephens was continuously fielding requests for guidance as regional director of the Missoula Small Business Development Center. The volume of calls for help only increased when she joined the BEAR program alongside Kier and Gladen. Stephens said her client meetings doubled this spring, from 140 in February to 278 in April. Same for the number of new clients, which rose from 14 in February to 27 in April.

Stephens was able to walk many of those clients through financial projections with screen sharing on Zoom, and she felt fortunate that the Missoula SBDC had hired a second staffer just prior to the pandemic, who helped shoulder the workload remotely from Kalispell while waiting for the COVID situation to settle enough to move to Missoula. Funding from the CARES Act also enabled Stephens’ office to hire a third person specifically tasked with assisting businesses impacted by the pandemic through the end of the year. Based on her interactions, Stephens said uncertainty was by far the biggest stressor facing Missoula business owners early on.

“Folks would say, ‘Well, I don’t know if I want to apply for the PPP because I don’t know what I need,’” Stephens said. “They didn’t know how much time to plan for, they didn’t know how much cash flow they would need because they didn’t know what was coming in the future.”

THE PANDEMIC PIVOT

McQuilken was lucky. Her long-running relationship with her banker and others put her in a strong position to navigate the immediate financial hurdles of Montana’s shutdown. But not all the challenges facing businesses are about money. For McQuilken, the value of the BEAR program manifested as a familiar and trusted face: Christine Littig, a past president of the Missoula Downtown Association and former owner of two Missoula businesses now serving on the BEAR roundtable. Littig arrived at Betty’s Divine in person, masked and maintaining a good 10 feet of social distance, to offer McQuilken suggestions on how best to prepare the shop for new health and safety protocols.

“Christine came in, did a site walk with me and helped me do some rearranging, looked at my ideas and challenged some of them and exposed other things and told me some were necessary,” said McQuilken, who held off on allowing customers into Betty’s Divine until a week after Bullock’s phased reopen began. “That was really helpful. One of our main things is we require all of our customers to wear masks, and I was definitely nervous reopening.”

Other Missoula businesses found the pandemic created opportunity and increased demand for their services, and positioned themselves via the BEAR program to offer whatever aid they could. Patrick Claytor, owner of the Missoula-based shipping company Big Sky Fulfillment, doubled his staff from roughly 15 to 30 in response to a rise in orders for the health foods, nutritional supplements and other goods his warehouse packages and ships on behalf of businesses nationwide. Claytor said he’s now poised to open a second facility on the East Coast by October, well ahead of his pre-pandemic projections..

Even so, Big Sky Fulfillment is “taking it a week at a time,” Claytor added, acknowledging that mail carriers and retailers nationally continue to struggle with disrupted supply chains, and that consumer trends could shift in the wake of the July 1 expiration of enhanced unemployment benefits. Even with that uncertainty, Claytor told his story of pandemic adjustment in an April 23 BEAR program video, and continues to offer himself as a resource for Missoula businesses trying to implement changes of their own.

“If there’s a shop downtown that has some sort of website but they don’t take online orders now and they want to figure out how to increase that so that they can move product and take care of customers, that’s the type of expertise we have,” Claytor said.

With the state well into phase two of its economic reopening, Missoula businesses are increasingly shifting their attention from the economic hardships of a shelter-in-place order to the mid-term obstacles now beginning to manifest. For many, the continued threat of COVID-19 necessitates changes that could last for at least another year. The BEAR program has taken to encouraging owners to think of their businesses as startups again, returning to basic questions about customer demographics, staffing needs and near-term operational goals that any starting entrepreneur needs to tackle. The advice fits with the shift in feedback Kier notes from Missoula businesses, who several months ago were concerned with sudden financial strife, but are now grappling with an unknown pace of recovery and the need to balance economic engagement with public safety.

“I think it was easy in the first few weeks of this to think that if we sheltered in place for two weeks, and we poured money into the economy for a month or two after that, that we would immediately ramp back up to something like a trajectory of a normal economy,” Kier said. “It’s much clearer to all of us now that there’s a lot of uncertainty on the path ahead and we need to redefine the way we run our businesses and our institutions over a much longer time horizon. That’s a different type of planning and a different approach to thinking through how to respond to the crisis.”

At Betty’s Divine, McQuilken plans to continue selling clothes through social media, an experience she says she’s finding far more intimate and immersive than in-store interactions. She now views the shop’s physical space as a “passive shopping” experience, and has found that when she gets stuck on a challenge, it’s because she’s approaching it from a pre-COVID, business-as-usual mindset.

Other Missoula businesses have already pivoted to survive not just the first months of the pandemic, but the months to come. Kier points to the Bonner-based pedicab manufacturing company Coaster Cycles, which switched its entire manufacturing line to producing face shields to help address shortages of personal protective equipment. The Good Food Store issued a requirement in April that all customers wear face masks, a decision that persisted right up to the Missoula City-County Board of Health’s July 9 issuance of a rule requiring face masks in all public indoor spaces. Littig noted that Missoula shops are collaborating independently of the economic development community to help each other tackle issues arising from public health measures, including how to effectively communicate the need for facial coverings to customers.

“Everyone’s realizing, OK, this isn’t just a three-month thing,” Littig said. “We’re going to have to dig in and learn to work with each other side by side, in unison … being willing to have discourse with each other to get through this, because it’s going to be two to three years of figuring out how we get back to a place that feels comfortably operational and consistent.”

LONG-TERM PROSPECTUS

In response to the shifting focus among businesses, the BEAR program has made a pivot of its own. Its website continues to take requests for financial assistance through its online portal, but in late June BEAR launched an anonymous question-and-answer initiative to address new and ongoing concerns from local business owners.

Littig said the program fielded nine questions the first week, which it answered during a Facebook Live event on June 18 featuring Littig, Gladen and other business owners and accounting professionals. The Facebook Live discussions will continue every Thursday as questions roll in. The anonymous nature of the weekly Q&A has proved critical in making business owners feel comfortable, Stephens said, as some may be hesitant to ask about compliance-related issues or reveal their tax situation in a public forum.

“The other things that people don’t like to ask are things that are socially controversial, like do masks really make a difference,” Stephens added. “In an environment where people might be afraid of either societal response or regulatory response, it can be great to have an opportunity to ask those questions.”

Separate from its work with the BEAR program, the Missoula Economic Partnership has also reconfigured its response to the crisis. It’s now in the early stages of rolling out a comprehensive Safer Missoula campaign, complete with a standalone website, to encourage compliance with citywide public health precautions and offer one-stop shopping for safety guidelines for businesses and residents alike. Kier said his team hopes to ramp up public awareness of the need for mask wearing, hand washing and social distancing with downtown banners, billboards, storefront signs and television and radio ads, “so that as summer progresses and students come back, it’s really clear what we need to do collectively as a community to maintain public health and get through this together.”

Kier has also found that the BEAR program continues to function as an invaluable two-way information conduit.

“Not only is BEAR taking collective information from a much bigger group of professionals and giving that professional feedback to each business,” Kier said, “but BEAR brings back the questions and the challenges that each business faces to the bigger group of partners around the ecosystem. What that means is there’s this incredible dialogue around service providers, but we streamline and deliver really succinct and clear responses and answers and resources to each individual business that needs help.”

Montana’s economy isn’t just reacting to the crisis. Gladen notes that coronavirus response has actually spurred new entrepreneurial ideas, and several startups have already approached Blackstone LaunchPad for the usual suite of services it offers to new businesses. One of those entrepreneurs is Sean Puckett, a Helena-based portfolio manager who used his spare time during the shelter-in-place order to forge ahead with a new app he’d been keen to develop. Puckett said he’s been conducting research-phase interviews via Zoom since the pandemic arrived in Montana, and hopes the app will become a valuable tool for crowdsourcing small donations to causes aligning with the United Nations’ 17 goals for sustainable development. To do that, Puckett plans to help individuals with limited discretionary income find nonprofits where their small contributions can have the most direct impact on issues like poverty, world hunger and sustainable oceans.

“When all of this started happening, you start thinking about what’s the world going to look like after,” Puckett said. “How can technology change that, and what are going to be behaviors of people, and how is the political landscape going to look? Trying to guess about what that’s going to be like, just even thinking about that spurs innovation, because you start thinking about all these different ways to solve problems … In a sense, the crisis probably got my brain thinking a slightly different way.”

Gladen isn’t surprised to see entrepreneurs emerging from the pandemic with new startup ideas. Crises have a tendency to spur innovation, whether that innovation focuses on making a long-term difference or providing near-term assistance. Ultimately, Littig believes individual- and community-level innovation will be a deciding factor in how well Missoula businesses withstand the economic ravages of COVID-19. The Missoula Economic Partnership, the Missoula SBDC, the Missoula County Economic Recovery Task Force, the BEAR program — all these groups can serve as Missoula’s guides, its cheerleaders, and incubators of different approaches to doing business in a town struggling to define its new normal.

Inevitably, though, the task of reimagining business in a world restructured by a virus falls to the individual who started the business in the first place.

“It’s hard to hang on to imagination when there’s so much burden and stress and we’re inundated with negativity, a downpour of chaos on multiple fronts,” Littig said. “But really it’s important at this time that businesses look at themselves as needing to be adaptable, ready for change.”

The Article was originally published on If you could do it all over again…